Extended Interview with a Founding Teacher of A-School, Tony Arenella

/The Full Interview Conducted by Film Director Lesley Topping for Our Film, From the First Schoolhouse: A Scarsdale Story

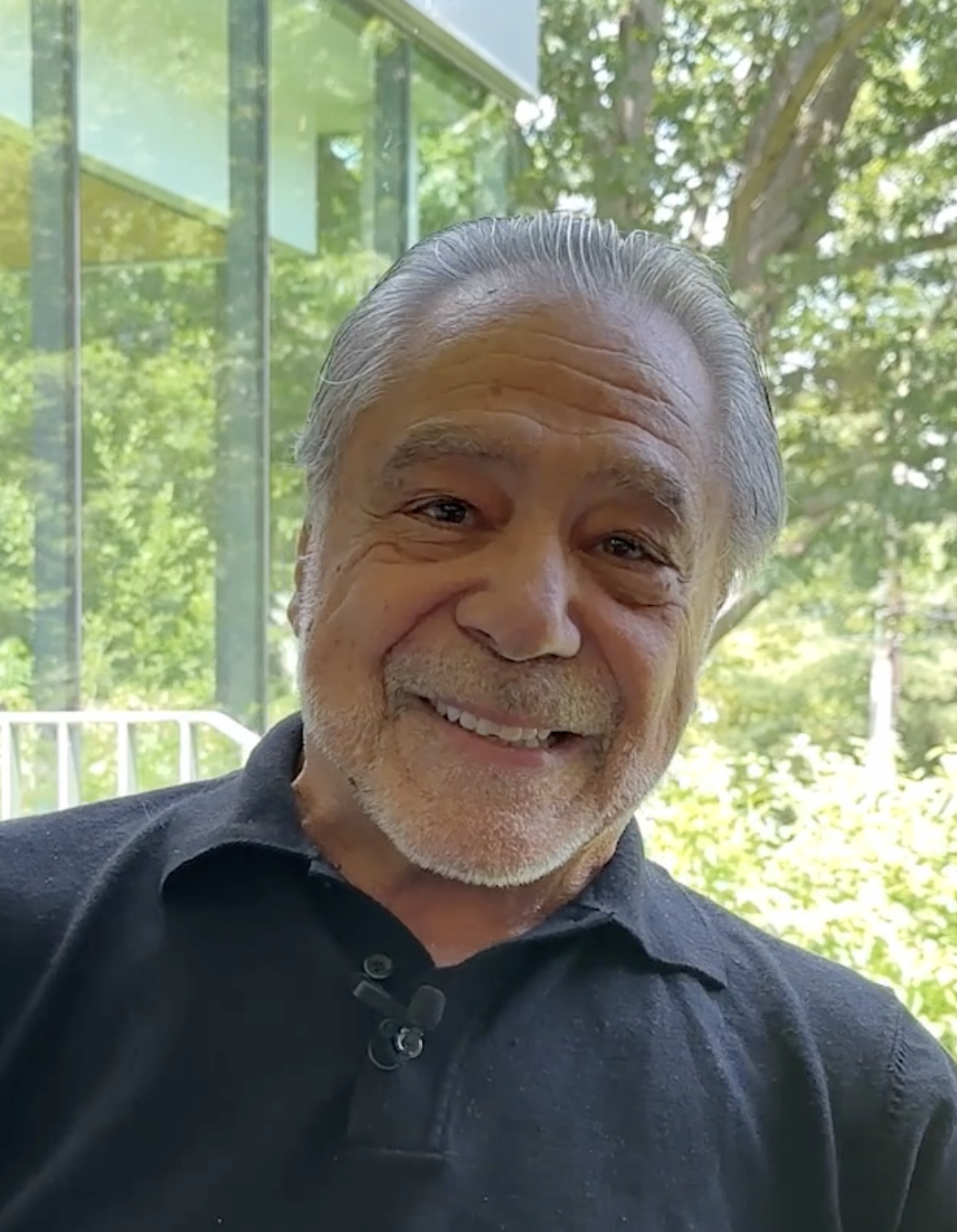

Tony Arenella is one of the original founding teachers of the Scarsdale Alternative School (A- School, or SAS), a unique community-based alternative school within Scarsdale High School. In this extended interview, Tony discusses the groundbreaking ideas that shaped the school in the seventies and continue to contribute to its success today.

About the A-School

Tony on the steps of the Scarsdale A-School, 1977 Scarsdale High School Yearbook

Founded in 1972, the A-School is known for its progressive, student-centered approach to education. With small classes and an emphasis on collaboration, discussion, and critical thinking, the school fosters curiosity, independence, and a strong sense of community.

About Tony Arenella

Tony Arenella was one of the founders of the Scarsdale Alternative School. He received a bachelor’s from Columbia College and a Master’s in Education from Harvard University, and started at Scarsdale Schools teaching English in 1969. In 1985, he succeeded Judy Codding as the director of the A-School, serving in that role until he retired in 2003.

Beginning with only sixty-two students, three full-time teachers, and several part-time teachers, the early team developed the groundbreaking philosophies and structures that still shape the A-School today. Tony’s dedication kept the school grounded in Lawrence Kohlberg’s principles of the “Just Community,” and also helped sustain the school during challenging financial times.

Interview with Tony Arenella

Extended bonus content with Tony from: From the First Schoolhouse: A Scarsdale Story, a documentary on the history of the Scarsdale schools.