The Cudner-Hyatt House

The Cudner-Hyatt house, one of Scarsdale’s earliest pre-Revolutionary farmhouses.

The old house at 937 Post Road in Scarsdale (across from the Immaculate Heart of Mary Church) is known as the Cudner-Hyatt House. It is one of Scarsdale’s earliest pre-Revolutionary farmhouses. The campaign to save the house from being demolished, and its restoration in the 1970s and 80s initiated the Scarsdale Historical Society. The Cudner-Hyatt House became a 19th century museum. The 1828 Quaker Meeting House was also moved to the property alongside of it. Both created a living history center for students and visitors throughout Westchester.

The Quaker Meeting House (left) was moved to the Cudner-Hyatt property in 1977.

When changes over the years in the schools’ curriculum resulted in fewer visits and the maintenance and staffing of the houses became more challenging the Society made the difficult decision to close the museum. But its legacy continues here.

Take a video tour of the museum with Barbara Shay MacDonald, our historian and a founding member and trustee of the Society.

The History of the Cudner-Hyatt House

Caleb Hyatt remembers the farm of his childhood in 1890 when he was 10 years old.

The Cudner-Hyatt house and property dates back to the tenant farmer days when it was part of Caleb Heathcote’s manor. The farm once included more than 200 acres stretching from the Post Road to the Bronx River. The house was deeded to Mikiah Cudner in the mid 1700s. For over two centuries, only two families, the Cudners and the Hyatts, lived in the house. Their stories reflect the history and transformation of Scarsdale from the eighteenth century to modern times.

When the last owners, Elvira and Caleb Hyatt, died in 1972, a group of concerned residents campaigned to preserve the legacy of the farmhouse. They successfully applied for the house to be registered as a historical site. They formed the Scarsdale Historical Society in 1973 to buy the property with the intention of making it a community center and museum.

The Cudner-Hyatt House museum was furnished to recreate a 50-year period between 1836 and 1886. This was the period of time when the Hyatts moved into the farmhouse until the death of Sarah Cornell Hyatt. She was grandmother to future generations that would live in the house until 1972.

Cudner-Hyatt house booklet

To find out more about the history of the Cudners and Hyatts, read the booklet published by the Scarsdale Historical Society celebrating the opening of the museum in 1987. Click here.

Left to right: Sarah Cornell Bates Hyatt, unidentified woman, Sarah Odell Hyatt.

Sarah Cornell Bates Hyatt (1854-1939)

This article by Barbara Shay MacDonald was published in the Scarsdale Historical Society Journal, 1993.

While I was researching the Bates Quarry, I found myself engrossed in the story of the Bates family who lived in the 1732 farmhouse diagonally across the road from the Cudner-Hyatt farm, just over the Eastchester line. I was intrigued by the story of Sarah Cornell Bates Hyatt who was to marry Oliver Avery Hyatt in 1879.

In the 18th century, Sarah’s grandparents, John and Sarah Cornell Bates had been friends of their neighbor the Cudners. They are buried side by side in the Methodist Cemetery in New Rochelle.

Sarah Odell Hyatt, (1807-1886) wife of Caleb, mother of Oliver Hyatt. She was the first generation of Hyatts to live in the house

Ten children had been born to John and Sarah, the sixth of whom was Alfred, our Sarah's father. After his father died, he joined the second class of Wesleyan College, a Methodist institution, for one year. When he was in his forties, he married Lucy Whitney, a bright young tutor from Vermont.

Their first child, Sarah Cornell, was born in 1852 in Lloyd’s Neck, Long Island. When little Sarah was ten years old, her Eastchester uncles died and the family moved to the Bates Homestead on Post Road, the home in which Alfred had been born.

There was a marble quarry on the 200-acre farm, but it was only intermittently operated. The Bates men were not builders or stonecutters and it was difficult to find someone to operate it.

Bates Marble Quarry

Located where Dunwoodie Little League field now stands, the quarry was filled in after World War II. Alfred’s office, the blacksmith shop, the stone sawing shop, quarry office and superintendent’s building were located on the north side of Summerfield Street, from Dunwoodie to Brook Street. Vestiges of those buildings can still be seen. Even though the farm was small, Alfred was said to have accumulated a fortune raising horses, grain and produce.

The Bates Marble Quarry

The Bates farmhouse had been built close to the road, facing south. The original house greatly resembled the Underhill House at 1020 Post Road with its Hudson River dormers, Dutch kick roof and porch and pillars. Over the years there had been two successive easterly additions and Alfred made many improvements.

The Bates homestead, the original house was built circa 1732

A charming family memoir written by Aymar Embury II, Bates’ grandson, tells us that at the rear of the house there was a marble path that ran to the privy. “Delightful little whitewashed shingle building, glorified in the spring by a magnificent wisteria. It was divided into two parts—the left for women and the right for men, and each contained a scrubbed white bench, very comfortable, with holes of various sizes to conform to the ages of the users, and with scrubbed pine boxes ·containing cut up newspapers and corn cobs.”

It is noteworthy that when the children were grown and married, there were often as many as 50 people for holiday dinners. The dining room was the biggest room in the house, and the most important. It contained a large black horsehair sofa, and there every morning at eleven o’clock, Alfred used to lie down, cover his face with a newspaper and go to sleep. It was a time when the rest of the family tiptoed around the house.

Standing: Alfred Bates. Seated, left to right: Edna Bates, Lucy Bates, John Bates, Anne, Eliza Bates

Aymar tells us that the front of the house was a great square lawn, studded with honey locusts, and decorated with peacocks.

“I admired the peacocks most dutifully, but my real admiration was reserved for the gigantic pigs in the orchard at the opposite end of the lawn. They were really dangerous animals.”

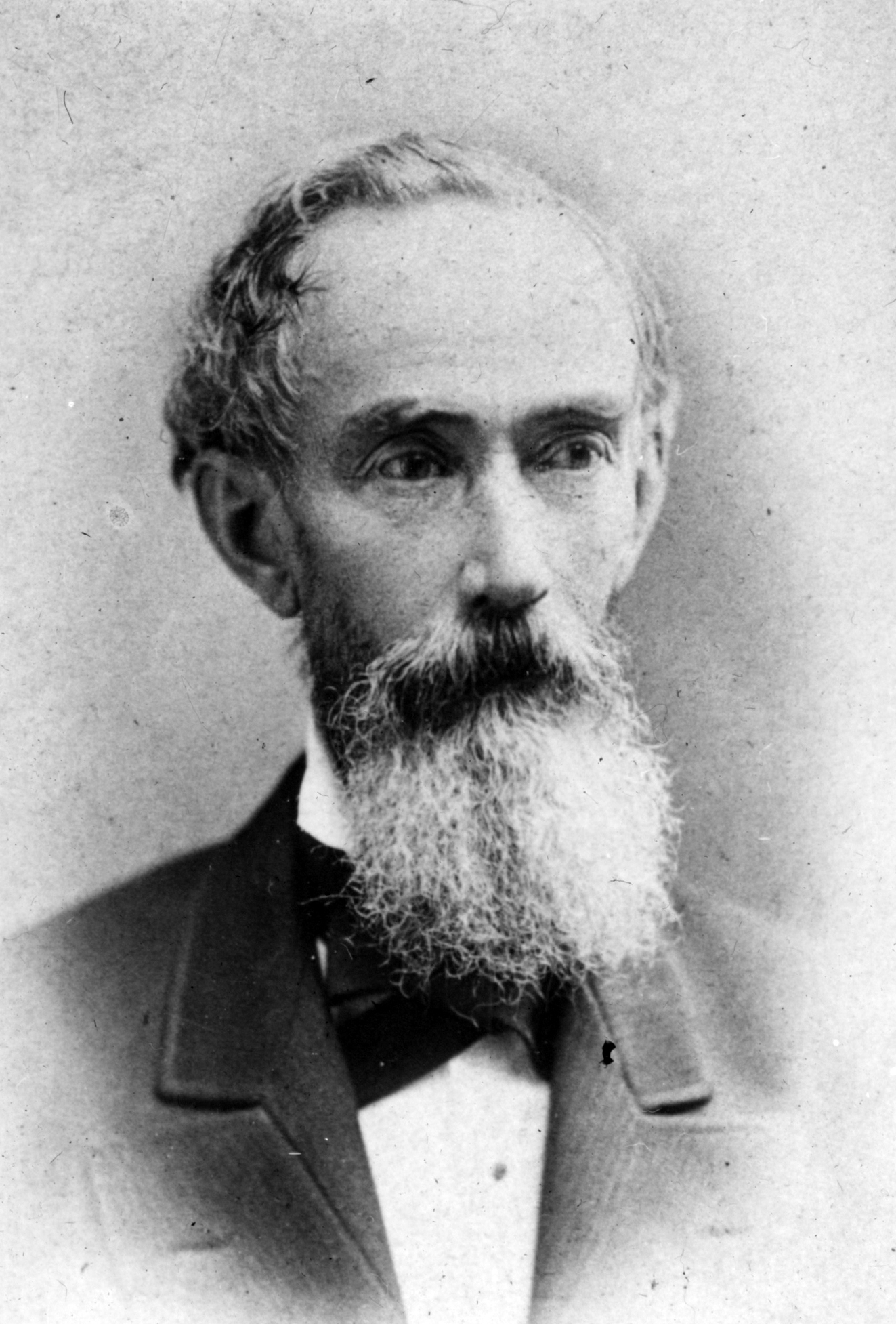

Alfred Bates, Sarah’s father.

Alfred Bates, the father of Sarah, was a tall, thin, gaunt-looking man who never weighed more than 116 pounds.

He was a gentleman farmer who seldom wore anything simpler than a black Prince Albert coat, a low-cut vest, a white shirt with a string tie, and black half boots, very- highly polished. He admired his beautiful horses, and late in life had a pair of white trotting mules which he used to drive down to Magown’s Pass Tavern, hitched to a silver mounted sleigh by a silver-mounted harness.

Lucy and Alfred Bates cared deeply about education for their 11 children. They were taught by private tutors; among them were some men of distinction—Bourke Cochran, who was afterwards a very important political figure, and Clarence Cooke, who was later a professor of language at Columbia. All of the boys, except George, graduated from Columbia: Alfred was an engineer, Henry a lawyer, John a physician, and Willy, although a Columbia graduate, became a farmer.

George was to work his way up in Rogers Peet, a prestigious men’s clothing firm, to become vice president and general manager, and was also the first mayor of Mamaroneck.

The girls’ education, if not completely formal by today’s standards was extraordinarily good. Everyone in the family could sing or play an instrument, most of them both. All the girls could paint and draw and they could all write excellent English in beautiful script. The boys used to get up at three in the morning, drive the teams with farm produce to the markets in Harlem, sell the produce, stable, the horses, go to college which was nearby and return home after dark.

A rear view of the Bates House, circa 1896.

Of the six girls, Mary Edna married a Connecticut Clergyman named Kirschsten; Lucy Married Edward Bonnet, a very wealthy Cleveland biscuit manufacturer; after their marriage they moved to California and bought several orange groves; and Fanny Miller married her brother Henry’s Columbia classmate, Aymar Embury, an architect. Two of Sarah’s sisters never married. Irene was an Episcopal nun and teacher. Ann Eliza, crippled from a childhood accident to her spine, made her living as a companion, courier or governess.

In the 1920s when she was over 60, she and a Mrs. Billings, whose companion she was, went overland from Baku on the Caspian Sea, through Afghanistan into India, without male escort, except for hired guides and camel men.

Ann didn’t seem to think this was dangerous: “We were armed; Mrs. Billings carried a pistol and I carried the cartridges so there wouldn’t be an accident.”

Now we come to the reason I wrote this story—the major connection between the two families who lived as neighbors at the gateway to Scarsdale. In 1879, living at the Hyatt Farm were Caleb, a 42-year old bachelor surveyor, Elisha 44, who remained single and was to live with Caleb until his death in 1910, their sister Sarah, age 36, and their widowed mother Sarah Odell Hyatt, 72. In addition there was a 13-year old servant girl, not an unusual occurrence in those days.

When 10-year-old Sarah Bates had moved to her family’s homestead, Oliver was 25, but now their 15 year age difference didn’t seem so great.

In April of 1879, Caleb and Sarah were married at St. James the Less Church, and Sarah became the third Sarah living at the Hyatt farm. Sarah Hyatt remained with the couple until after her mother’s death in 1886, when she moved to Dobbs Ferry.

In January of 1880, Caleb, the first of the couple’s five sons, was born. Thirteen months later in February, 1881, Alfred Bates was born. In June of 1882 Oliver Avery, a third son, was born. In May of 1883, little Oliver died a month before his first birthday, and the following week two-year-old Alfred also died, perhaps of the same childhood disease that had taken his brother.

Sarah’s surviving sons, John, Caleb, George.

A year after the death of the two children, a fourth son, George Valentine, was born. In the fall of 1888, when Sarah was pregnant with her fifth son, another tragedy befell the families: Sarah’s father Alfred had a new colt, one “Starlight,” who was so beautiful that Alfred decided he would start to break him in himself. He was 75 at the time and his wife Lucy, who was with him in the training sulky, was 63. They rode down Brook Street, the southerly border of their farm. As they neared the railroad crossing, a train blew its whistle, Starlight bolted, getting across the track, but the sulky was hit and the Bateses were killed. They lie in a double grave at St. James the Less. John E. Hyatt, named for Sarah’s doctor brother, was born a few months later in February, 1889.

Oliver Hyatt with Col. Alexander Crane. They were vestrymen at St. James the Less Church, 1923.

Sarah’s Eastchester home and farm were sold after her parent’ death. Sarah combined her 75-acre legacy with Oliver’s house and farm, then 37 acres, and sold them in 1891 to the North End Land Subdivision. The couple bought the farmhouse back, without much of the acreage, only four days later. They built a new house, leasing their homestead, and lived in several houses in Scarsdale, but never in the old farmhouse again.

One cannot be exactly sure what happened to the beautiful Bates home, but less than 20 years after the couple’s death a headline appeared in the Scarsdale Inquirer, on March 21, 1907: “Old Eye Sore Will Be Removed.” The article went on to say that “all Scarsdale will rejoice at the announcement that the Century Homestead Hotel is to be eliminated from the landscape.” Apparently the Bates home had been converted into a hotel. The purchaser of the hotel said he would remove the hotel and the outbuildings, clean up the property, and establish a high-class residential district. The plan was to sell the Homestead with nine lots. It is said that the hotel burned down before it could be sold.

Scarsdale Inquirer, March 21, 1907

One can only imagine Sarah’s feelings when she looked across at her once gracious home.

As Sarah’s children grew older, she began to become involved in the community. St. James the Less was the center of her activities all of her married life.

She was one of the founders of the Scarsdale Women’s Club, and founded the Music Section there in 1912. She had previously been the founder of the Scarsdale Nursing Association in 1905. Sarah and Oliver then moved in 1924 to live in Scarsdale’s first apartment building at 10 East Parkway. They were up on the second floor at the comer of Popham Road. They had already sold the old Cudner-Hyatt homestead to their son, Caleb and his wife Elvira that same year for $100. Sally (Sarah) Hyatt Bullen, Caleb’s daughter who was born in 1915, remembers that when her brother had scarlet fever, she and her sister Peggy stayed with their grandmother and she taught them to play bridge. Sally also remembers holidays when Aunt Irene (she was the youngest Bates and outlived all the others) and Auntie Hyatt (Sarah) came for dinner. Sarah remained close to her brother George all her life.

During the last year of his life, Oliver Hyatt sat peacefully in a wheelchair at the comer of Popham Road and East Parkway watching the stream of traffic coming over the roadway whose construction he had supervised as road commissioner on land that had belonged to his father. He died at the age of 91 in 1928.

Sarah lived 11 years after her husband. She stayed in Scarsdale for several years, and then joined her son John in California, where she died peacefully at John’s home on September 24, 1939 at the age of 87. She was buried in the family plot at St. James the Less in Scarsdale. Thus ended the entwined lives of the two families, cemented by the beautiful 65-year marriage of Sarah Cornell Bates and Oliver Avery Hyatt.

The 1828 Quaker Meeting House

The 1828 Quaker Meeting House were the offices of the Historical Society and home for many exhibits. It has its own unique history. Originally on Weaver Street it was moved, reconstructed and restored beside the Cudner-Hyatt House Museum in 1977.

Amy and Paul Griffen of Amawalk meeting, relatives of Scarsdale’s Griffens. Photos by Rosch, courtesy of Haviland Record Room

“Members of the Religious Society of Friends were among the first settlers of Scarsdale in 1723, when John Cornwall (an early version of the Cornell name) started farming on some of the land he bought ten years earlier,” writes Mary Ellen (Mickey) Singsen, our Quaker Advisor and historian of the present-day Scarsdale Friends’ Meeting. The Quakers erected their first house of worship in Scarsdale in 1768, when they moved the 1739 Mamaroneck Meeting House “on the Westchester Path, now the Boston Post Road, to a wooded lot on Weaver Street at Griffen Avenue.”

According to Mickey, about one-third of colonial Scarsdale’s residents were part of the Quaker community. In addition to Cornell, many families had names still familiar to us because streets and other places in Scarsdale, Greenburgh, New Rochelle and White Plains were named after them, including Griffen, Secor, Tompkins, Carpenter, Haviland, Burling, Palmer, Carhart and Ferris.

In 1828, a theological dispute led to a split between the “Orthodox,” who “placed great stress on the Scriptures, were evangelical in tone and emphasized the historical Christ” and the “Hicksites,” named after Elias Hicks of Long Island, who “relied on the authority of more mystical Inward Light as that part of God which is in every person” (Singsen, The Quaker Way in Old Westchester, pamphlet, 1982).

The split, which lasted until 1955, divided many families; lists in Helen Hultz’s Scarsdale Story: a Heritage History show members of the Cornell, Griffen, Palmer and nearly every other Quaker family of that era on both lists.

‘Birth’ of the 1828 Quaker Meeting House

Fascinating accounts of the actual split are described in the minutes of the Friends Meeting, as quoted by Helen Hultz:

“July 3rd 1828: Mamaroneck preparative meeting held under the trees in the meeting house yard,in consequence of friends, being deprived of the use of their meeting house by those who have separated from us... And knowing from the report that disaffected members of our meeting have put Locks upon the doors of the meeting house and keep them locked…” Subsequent meetings, “friends still being deprived of the use of their meeting house”, were held in the yard, under the trees on August 7 and in a stable on September 4.

By September 10, a remedy, noted in the minutes of the Purchase Meeting, was proposed: “Friends of Mamaroneck preparative meeting...are left at liberty to put up a suitable building in the west end of the yard for their own.” Evidently those Hicksite members of the Mamaroneck meeting who had locked the doors to the Orthodox decided to comply with this directive, for on September 19 their minutes stated: “When those of our friends, who have separated themselves from our society, were about laying the foundation of a new meeting house in our front yard, we made them the following proposition... We will furnish them with a piece of ground to the west of and adjoining the school house lott containing one half as much ground as it now contained in said meeting house lott or if they prefer it, as much land adjoining Samuel J. Cornell’s, and give them good title to the same…”

By October 2, the Orthodox minutes relate, “It was united in believing it best that a building should be erected for a meeting house agreeably to the minutes of the monthly meeting, and Henry Griffen, Daniel Griffen, Elijah Tompkins, Richard Carpenter and Samuel S. Cornell are appointed to superintend the building, and they are authorized to have on the meeting’s account such sum of money as may be necessary for the purpose.”

Amazingly, in two months—much less time than the year it took the Historical Society in 1977 to dismantle, move and reassemble the Meeting House!—the minutes of December 4, 1828 state:

“The new meeting house being now completed the preparative meeting was held in it, and Samuel S. Cornell and Benedict Carpenter were appointed to take necessary care of the house and yard for one year.”

In the years following, the two groups and their meeting houses existed side by side. According to Mickey Singsen’s Quakers in Scarsdale (pamphlet, 1978) a map drawn in 1853 showed “a new road on or near the Line between the towns of Scarsdale and Mamaroneck and leading from the White Plains and Mamaroneck Road to the New Rochelle,” later called Griffen Avenue. They were surrounded by a “solid row of Quaker owners.” However, “in the last third of the 19th century, farmers on Quaker Ridge began to sell their land. In 1871, William Cornell sold William H. Stiles the more than 157 acres which surrounded the two meeting houses. Gradually, the farmland was purchased by wealthy New Yorkers for summer residences... By 1911, the changeover was nearly complete.”

Hannah and Alnathan Carpenter relatives of 19th Century Scarsdale Friend Benedict Carpenter. Photo by Rosch.

To learn more about Quakers in Scarsdale click here.

Produced by Lesley Topping with Barbara Shay MacDonald.